Created July 2001 Updated: 01 Dec 2017

Written and researched by Mike Kemble

Captain Walker RN

"Let who

will speak against Sailors; they are the Glory and Safeguard of the Land.

And

what would have become of Old England long ago but for them?"

| Captain Frederick "Johnny" Walker, CB, and 4 times

DSO, was from September 1941 to September 1942, Commanding Officer of HMS STORK.

The Second World War was fully in its stride when he took command. When Captain

Walker addressed the ship's company, he said that he had not been able to sail

during the war, working in Whitehall, but he then made a prophetic statement. He

stated, "I have some ideas of my own" in reference to using counter measures against

U-Boats. A simple enough phrase, perhaps, but those words were soon to be put

into practice when, as Senior Officer of the 36th Escort Group, the ships under

his command sank 5 U-Boats in 10 days whilst escorting Convoy HG76 from England

to Gibraltar, on the return trip he sank 4 more! And this was only the

beginning! It is not generally realised how close the toll on our Atlantic convoys from 1940 until early 1943 came to bringing Britain to her knees. Without the convoys, no supplies; without supplies, certainly no Second Front. Captain Frederic Walker, CB, DSO***, RN devised and employed tactics which were the only sure means of combating and ultimately defeating the U-boat wolf packs, and it was only when the Lords of the Admiralty came to employ these tactics that the U-boats were finally defeated. *** three bars |

|

| No one did more to regain control of the North Atlantic than Captain Walker. His relentless battles with the U-boat wolf packs, amounting almost to a personal duel with Admiral Donitz, is an epic saga which has long deserved a larger piece in our nation’s history, though he did achieve the rare distinction of winning the CB, DSO and three bars. |

|

The forward from the

book Walker RN by Terrence Robertson, now out of print, by Admiral Sir

Alexander Madden, K.G.B., C.B.E., R.N. CAPTAIN FREDERIC JOHN WALKER, ROYAL NAVY, was a forthright and practical man, full of faith and action in every thing he undertook, We happened to be serving together at the time when he heard that he had not been selected for promotion to captain. He suffered great disappointment: but he met this problem without visible distress and in the same uncompromising way that lie met, and overcame, all problems in his naval career. I feel sure that his countless naval friends would wish me to record our joy, for it was nothing less than that, when his superlative work was, later, regarded with total acclaim. This book illumines his remarkable character and personality. To those in the Royal Navy who, like myself, were privileged to know him well, there seemed to be nothing missing from his armoury of qualities; he was a high-principled, courageous, modest and kindly naval officer, who looked exactly what he was, an outstanding leader of men. It would be an impertinence for me to try to add to the great tributes paid to him by famous war leaders. But as a contemporary of his, I am indeed happy to have this chance of recalling the deep admiration and affection in which, over many years, I held this unforgettable youth and man. His place in naval history is assured. Plymouth, 1956 |

| Frederick John Walker was born on 3rd June 1896 and entered the Royal Navy on 15th June 1909. He passed out top of his class at the Royal Naval College at Dartmouth, received the King's Medal and did well in his examinations in the training cruiser. He went to sea in June 1914 as a midshipman in the battleship HMS Ajax and stayed with the ship until he was promoted to sub-lieutenant on 1st January 1916 and moved to HMS Mermaid based at Dover. In 1917 he moved to HMS Sarpedon, which was part of the Grand Fleet. At the age of 21, he became involved in the battle against the U-boats that was to dominate his remaining time in the Royal Navy. In 1919, Johnnie Walker married Eileen Stobart and together they had three sons and a daughter. At the end of the First World War, Walker was sent to HMS Valiant as a watch-keeping officer. In 1921 he began to make a determined effort to learn everything he could about a new subject in naval warfare, anti-submarine operations. He was one of the first volunteers to go to the specialist courses at the newly formed anti-submarine school, HMS Osprey at Portland. He completed the course and was duly sent off to sea for six years, 1925-1931, in the largest ships, as far away from home as possible. Anti-submarine warfare was not a fashionable or glamorous branch and the least likely route for promotion to high rank at that time and was considered by many as a backwater. He was appointed Fleet Anti-Submarine Officer in the Atlantic and Mediterranean Fleets. |

RNC Dartmouth. Image: 28 May 2007 |

| First he went to HMS Revenge, then to Nelson and finally Queen Elizabeth and during these appointments became increasingly disillusioned with peacetime service in the big ships, but finally in 1933 he was promoted, at the last moment, to Commander and given command of HMS Shikari, (right) an S-class destroyer fitted with Asdic. This appointment lasted for only six months and in 1936 he was appointed to command the sloop HMS Falmouth, used as the Commander-in-Chief's yacht on the China Station. It was a bad appointment for an officer interested in anti-submarine warfare. Nevertheless he managed to make the best of it and spent three years in this ship, moving about to suit the convenience of the C-in-C. During this time, Eileen was taken seriously ill and had to submit to two major operations when in China, and he was financially broke. Shortly after this he completed his time in the Far East and returned home, preceded by unenthusiastic reports. |

HMS Shikari 1929 |

| Walker now returned to the Valiant as a caretaker to keep her functional and by the time he left in early 1937 he had accumulated more bad reports. In 1937 he became Experimental Commander in the Anti-Submarine School in Portland (left), and was responsible for research and development of anti-submarine materials and methods, an appointment he held until the outbreak of the Second World War. It was one of the happiest periods of his life and the disappointment of missing the opportunity for promotion to Captain was offset by doing a job he liked and would prove to be invaluable within a few years. |

| For the first time, he was also able to take a family house and return to his wife and children in the evening. The German Navy circumvented the Versailles Treaty by building U-boats and training their crews in Holland, Spain and Turkey. By 1939 the Royal Navy had an escort fleet of 201, down from the 477 it had in 1918 and there were barely enough destroyers to screen the battle fleets and only 101 escorts to defended the vast fleet of merchant ships needed to supply Britain. The U-boat war opened violently with the sinking of the liner Athenia, without warning, and the carrier, HMS Courageous. Scapa Flow was penetrated and the battleship HMS Royal Oak was sunk at her mooring by U-47 (right). In the first three months the U-boats claimed 114 Allied merchant ships of 421,156 tons for the loss of nine U-boats. Walker was appointed Staff Officer Operations to Vice-Admiral B. H. Ramsay, based at Dover and was responsible for the safe passage of the British Expeditionary Force and troops across the channel. |

|

| The initial threat came from U-boats, but the Channel was blocked and they were barred from using the Straits of Dover as a route to the Atlantic, and only one U-boat got through. The Norwegian campaign cost the Royal Navy 18 escorts as well as the aircraft carrier, Glorious. When the Germans rolled into the low countries, the Allied armies fell back before them to Dunkirk. The evacuation from Dunkirk cost the Royal Navy, a sloop and nine destroyers sunk and nineteen more damaged. As the threat of invasion manifested itself in German occupied harbours, the defence of the convoys was sacrificed to defend England but as the threat disappeared the convoys' protection was returned although the level of sinkings had risen to horrifying levels. In June alone, 585,000 tons of shipping, consisting of 140 ships had been sunk. Walker pleaded to get to sea and finally, after the intervention of Admiral Ramsay, Walker finally came to the attention of the Commander-in-Chief Western Approaches, Admiral Sir Percy Noble, and was appointed to command the sloop HMS Stork (below) in September 1941. |

HMS Stork was a Black Swan class sloop |

| Walker's first charge was a convoy, HG.76 of 31 merchantmen and a fleet auxiliary that sailed on 14th December 1941. The first U-boat to come out was U-127, which was spotted by a Sunderland from Gibraltar when it left the Spanish coast late on the 14th. It was picked up by the Asdic (sonar) of HMAS Nestor and dispatched at 1100 that morning. Just after midnight on 15th December, the convoy made its first contact with the waiting wolf pack. A patrolling Swordfish picked up a U-boat, by radar, on the surface just ahead of the convoy and attacked with three depth charges, dropped flares and tried to warn Stork.. The ship's lookouts spotted the flares and heard the explosion, so she was already racing for the spot at full speed with Rhododendron in pursuit. |

| The two ships hunted for the submarine but it stayed submerged. The Commodore drove on the merchantmen mercilessly, unmolested. Seven U-boats were concentrating on the course line of the convoy and three more were on their way from the Bay of Biscay. HG.76 now moved beyond the cover of Gibraltar's aircraft and Audacity had six aircraft of which four were operational. Stanley sighted a Focke-Wulf during 15th December, which confirmed that the Germans were preparing to attack. The escorts Exmoor and Blankney would have to leave the convoy on the 18th due to fuel limitations. Walker asked Audacity to fly a search around the convoy at dawn on the 17th to break the wolf pack's usual routine of staying just out of sight to track the convoy and spring ahead at night on the surface. At 0918 one of the Martlets posted a U-boat 22 miles from the convoy and the escorts set off in pursuit of U-131, which altered course to evade the charging escorts, but ran into HMS Pentstemon because his hydrophones were defective and was bombarded by depth charges which caused damage, forcing the U-boat to leave the area to avoid the escorts. The U-boat surfaced later on and repositioned for another attack. Just as Walker was about to lead his ships back to the convoy and prepare for a bad night, the surfaced U-131 was spotted by Stanley The U-boat was seven miles away, at the ships' guns extreme range and a very small target so the patrolling Martlet was ordered in. The Martlet attacked the surfaced submarine with machine guns, was hit and crashed into the sea. It was twenty minutes later that a number of hits from the four ships penetrated the hull eight times. U-131 sunk and 55 men survived and were picked up by Blankney and Exmoor. |

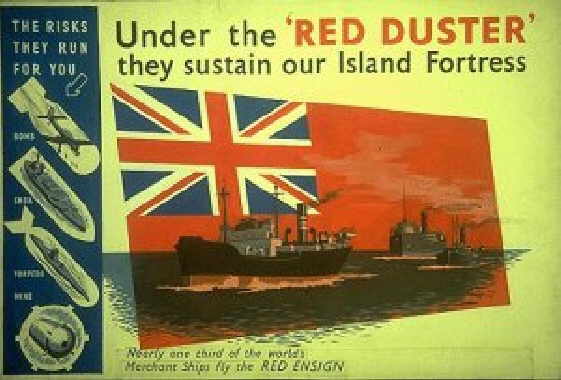

Survivors being rescued from the Atlantic Wartime Merchant Navy Poster |

| Sub-Lieutenant Fletcher's body, the Martlet pilot, was picked up and he was buried at sea the next morning. The escorts took up their night stations. At 1401 that afternoon a signal had been received confirming that a U-boat in front was still shadowing the convoy. The convoy could expect a big battle as the U-boat was guiding in the wolf pack lying ahead. Overnight five U-boats had gathered in position for a full-scale attack with another three on their way to intercept. This was to be the first of the new style set battles. On one hand, the U-boats and Focke-Wulfs, on the other the slow merchantmen screened by the close escorts, the Support Group and the Martlets from the escort carrier. Walker was now at sea with his long-held belief that the offensive use of an air/sea striking force would give the best chance of doing the maximum damage to the U-boats while still providing the maximum protection to the convoys. |

Station X - Bletchley Park |

| The Admiralty's appreciation remained heavily disguised for fear of revealing the secret of Bletchley Park, which had by now broken the U-boat cipher, and confirmed Walker's suspicions about the U-boats nearby. The convoy was steaming in calm weather with excellent visibility. These unusual conditions led to an error in judgement by U-434, which had shadowed the convoy during the night. At dawn he was on the surface ten miles out, and could observe the tops of the masts of the convoy without danger of being spotted himself. He decided to close the convoy on the surface then submerge, to conserve his batteries and get into a commanding attacking position. At this moment, Stanley was prowling the deep field on the port side of the convoy. |

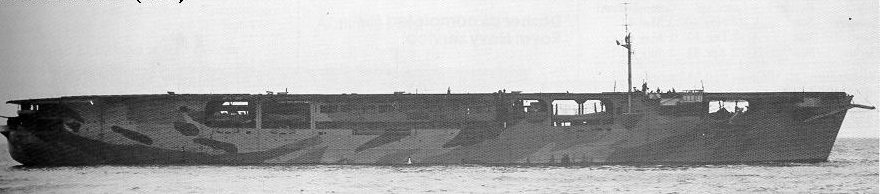

Audacity Blankney 1950 |

| Her Asdic was defective and she only had her lookouts to rely upon. One of the lookouts spied the submarine's periscope and Stanley turned to attack. Walker sent Blankney and Deptford to join her, and Exmoor was already on her way, but U-434 dived ahead of Stanley, who circled where she had dived and dropped single depth charges to keep the U-boat down and mark the position. Blankney established a firm Asdic contact and the two escorts damaged U-434 beyond hope. It was forced to surface and the crew abandoned the ship. The two escorts and Exmoor picked up the survivors. As the rescue was taking place, Focke-Wulfs appeared, circling out of range, but clearly visible. |

| Audacity flew off two Martlets in response and the Focke-Wulfs ran for it. Exmoor and Blankney were now at the end of their fuel reserves and had to return to Gibraltar, loaded up with ninety-three German prisoners. Pentstemon sighted the first U-boat of the wolf pack, U-574 when he came to the surface to check his position against the convoys. Walker ordered Convolvulus to join her and Stanley was already on her way. As they came up to the diving position, Convolvulus picked up the sound of torpedoes with her hydrophones and turned to port. Corvettes are fine sea-going ships but not very manoeuvrable and the two torpedoes skimmed the stern by twenty feet. U-574 dived and waited for two hours until the escorts gave up and returned to the convoy at full speed. U-574 surfaced and followed on the surface. Stanley was torpedoed and sunk, and then the submarine turned on the Stork and Walker charged the submarine. It dived and a chase ensued. The submarine surfaced to avoid Asdic inside Stork's turning circle and the two vessels circled in concert, Stork's 4-inch guns blazing until they could no longer be sufficiently depressed. After 11 minutes of these manoeuvres, Stork hit the U-boat a glancing blow on the starboard quarter, rolled it over and dropped a shallow pattern as the U-boat sank. The escorts then picked up the survivors and recovered 28 British and 18 Germans. During this, SS Ruckinge had been torpedoed on the port bow of the convoy. Focke-Wulf Condors continued to shadow the convoy, losing four of their number to Audacity's Martlets during the 20th. Samphire sunk the SS Ruckinge on her way back, the ship being too badly damaged to salvage. Stork had by now lost her Asdic dome, and had her speed reduced to ten knots because of damage in ramming U-131. On 21st December, the action started at 0900 with a Martlet reporting sighting two U-boats astern of the convoy. Walker decided to send the sloop Deptford and the corvettes Pentstemon, Vetch and Samphire. It was a bold decision; if they hunted for too long they would be unable to rejoin the convoy before nightfall. He asked for long-range air cover from the UK but none was available and the convoy was just inside their range. |

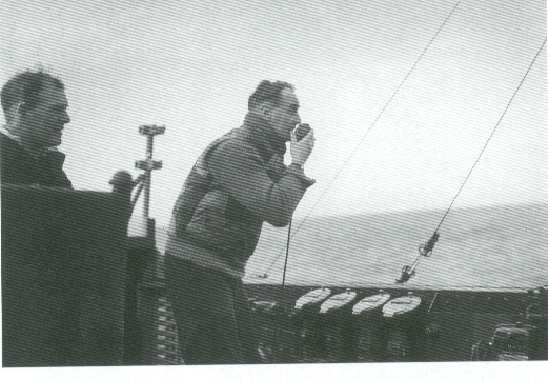

Walker on the attack, Navigator AC Ayes, is the other officer in the image Repairs in an Atlantic Gale |

| At 1126 the hunters rejoined the convoy finding no trace of the U-boats. The other U-boats were closing in and Walker decided to turn the convoy east and put the convoy out of reach of submerged U-boats, if they wanted to attack during the night they would have to run on the surface. Unfortunately the merchantmen did not understand and as Deptford staged a mock battle every merchant ship fired off snowflakes. At 2033 the Norwegian Annavore was torpedoed. Audacity, as normal, was zigzagging outside of the convoy without an escort, as Walker had only Stork and four escorts left and Stork had no Asdic. U-571 was shadowing on the surface and put three torpedoes into her. She listed to port and went down in ten minutes at 2210. Her commanding officer, eight officers and 63 of her complement of 400 were lost, and Pentstemon saved most survivors. Marigold chased down a U-boat on the convoy's port side, while Samphire and Deptford chased another on the starboard. During this battle, U-567 was sunk. Her commander, Lieutenant-Commander Endrass, was one of Germany's best and most experienced U-boat commanders. In her rush to get back to the convoy, Deptford ran into Stork's side and five German prisoners were killed in the collision. Deptford lost a six-foot square of plating about four feet above the waterline on the ship's bow. |

| The following night the convoy changed course three times, covered by a fake battle, and the first Liberator had been sighted earlier that day. The night passed quietly and HG.76 made port on 23rd December 1941. It was during the passage of this convoy that the foundation stone of the Captain's far-seeing concepts for the destruction of enemy submarines was laid. His ideas were soon to prove themselves. His tactics still form the principles of basic training in anti-submarine operations today. The nucleus of his determination to "seek out and destroy an enemy lurking below" was undoubtedly formed during the passage of HG. 76. Commander Walker went off for a few days' leave and learnt he had been awarded a DSO (below). After a short week at home, he presented his report of Proceedings at the Admiralty and to make his recommendations to the C-in-C Western Approaches, the Director of Anti-Submarine Warfare, Captain George Creasy and other senior officers. By 10th January, he returned to sea in temporary command of HMS Pelican to guard the Gibraltar convoys. He returned to Stork after she had been repaired and continued with the 36th Escort Group and during the escorting of HG.82 had his first experience of radar, coming away with mixed views, as the Type 271 proving accurate on HMS Vetch and the Type 286P, in the hands of Stork, was virtually useless. On 30th June 1942, Walker was promoted to Captain. |

Distinguished Service Order (with bar)

|

| At least 3, and possibly 4 more U-Boats were sunk by the 36th Escort Group before the Captain left STORK to take an appointment as Captain (D) Liverpool. Operating from Derby House. Whilst there he persistently badgered the Admiralty for a sea-going appointment, and in February 1943, he was given command of HMS STARLING, then being built in Glasgow. this at a time when the Allied need for escorts far outstripped the availability. The need in March 1942 was for 1,315 escorts; at the time less than half, 505, were available. To add to the woes of the Allies, from the beginning of 1942 Döenitz had been able to read the Allied Naval Cipher No 3 and Bletchley Park was experiencing problems with the Shark Enigma signals. Allied merchant fleet losses were appalling. The need now switched from lack of ships, aircraft and weapons to the need for new tactics, training and manning at all levels. American-built escorts would soon start to arrive in great numbers and the tactics for these new support groups would need to be completed and revised. In February 1943, HMS Starling was launched from Fairfield in Glasgow. When HMS Starling was due for commissioning, Captain Walker requested Admiralty that as many as possible of his former ship's company should be the nucleus of his new command. Although a large number of STORK personnel had been sent to other ships, almost half did in fact join Starling. After she was launched and carried out her gunnery and anti-submarine trials she was ordered to Londonderry to have the 291-radar set removed and the latest HF/DF gear fitted. This last-minute modification gave Walker the opportunity to avoid the training at Tobermory and train his own crew. |

HMS Starling |

The Hunters (Walker on the chase) and the Hunter turned Hunted - the U Boat |

|

Once at sea, Walker quietly but firmly clamped down with an iron hand. He made it clear that the task of the group was to destroy U Boats and that all they did from then onwards was directed to this end. The first paragraph of his Orders read: Second Support Group Operating Instructions (SG2) Object "The Object of the Second Escort Group is to destroy U Boats, particularly those which menace our convoys" This being a significant difference between those and the standard orders of an escort group which was "the safe and timely arrival of the convoy". Another abstract from Walker's Operating Instructions read: "Our object is to kill, and all officers must fully develop the spirit of vicious offensive. No matter how many convoys we may shepherd through in safety, we shall have failed unless we slaughter U Boats. All energies must be bent to this end." In the image above left, the gent with his back to the

camera, wearing a duffle coat is Donald Morris Ellis born 1920 in

Birkenhead, Wirral Merseyside. |

| Of the 21 million tons of Allied shipping lost during World War 2, 15 million tons were sunk by U-boats. The Allies retaliated by sinking 781 U-boats, which resulted in a loss of nearly 30,000 of the 40,000 Kriegsmarine personnel serving in U-boats. There was nothing accidental about this victory at sea. It was the direct result of a relentless pursuit of the enemy by the little ships, largely inspired by the brilliant exploits of one man, Captain Johnny Walker of the Royal Navy. Today, Walker is officially recognized as "the man who did more to free the Atlantic of the U boat menace than any other single officer." In 1941, Great Britain and Canada maintained 400 assorted escort ships along the Atlantic convoy routes, but the rate of U-boat sinking remained dismally low, approximately two per month. Then Johnnie Walker took command of an escort group of nine ships, two sloops and seven corvettes. These were major victories won without loss and by the use of unorthodox methods. |

| Since the outset of the war, it had been generally accepted that escorts would stay close to their charges to ward off U-boat attacks. Walker, then holding the rank of commander, had achieved his successes by ignoring this principle and hunting his victims well away from their quarry. He sank 2 U-boats 40 miles away from the convoy he was protecting. In high places at the Admiralty there were powerful forces at work seeking to brand Walker as a lucky heretic. Only his success and the unqualified backing of Admiral Sir Max Horton, the C in C of Western Approaches, prevented Walker from being posted ashore. While Admiral Horton was in a favourable mood, Walker persuaded him to try a revolutionary theory: Six modern, fast, specially equipped sloops, freed from the fetters of convoy duty, should be given a roving commission to hunt down U-boats in their most vulnerable grounds, the Bay of Biscay, which they crossed when beginning or completing their patrols, and far out in the Atlantic where they surfaced with immunity because the sky was clear of aircraft. In the spring of 1942, Walker took command of the Second Support Group, the first of these new striking forces. |

|

From the bridge of Starling, his own sloop, he drilled Wild Goose, Cygnet, Wren, Woodpecker and Kite until they became a team, swinging into action with few orders and no mistakes. The first few weeks were uneventful and gave the crews time to work up, before spending a few days in Iceland prior to leaving on 21st May. A typical Walker classic was the sinking of U-252, destroyed jointly by STORK and VETCH with the sending of a total of 8 signals, embracing 25 words. |

|

(Note:

an American site is claiming that they invented the Hunter/Killer Group idea in

1943! They did not, it was Walker. The US Banvy had no idea how to combat the U

Boat at this time. Also that they invented the hedgehog and the squid!):

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/nova/lostsub/hist1939.html#1943 |

Convoy off Halifax Nova Scotia, about to run the gauntlet of U Boats, to Britain |

| In June, Walker found an opponent worthy of his guile, Kapitänleutnant Gunter Poser, commanding officer of U-202. This U-boat was returning home after a special mission in which it had landed five Nazi agents in the United States on Long Island's Amagansett Beach. (These agents were all captured and executed) (See footnote at base of this page). It was U-202's ninth operational trip of the war, and 27-year-old Poser was a quick-witted, capable captain. U-202 transmitted a long signal while surfaced and the Group homed in on her position in line abreast. On June 13, Poser's officer of the watch sighted mastheads through the periscope and called him to the control room. Poser took over the eyepieces and immediately he thought them as destroyers. He ordered diving stations and within seconds U-202 was down to 500 feet. Poser had met Walker's Second Support Group hunting in fresh pastures. On Starling, the asdic (sonar) officer was already reporting contact. |

| The captain turned to the asdic officer and announced his intention to attack. Starling surged forward. The "ping" of the sonar beam echoing from the hull of U-202 coming faster as the range shortened. Then came the order to fire depth charges. Tons of high explosives rolled from the stern rails and shot from throwers on either side of the quarterdeck. Ten charges dropped through the water toward the enemy. For a few seconds there was silence. Then miles of ocean and the waiting sloops quivered as the blasting charges exploded. Huge columns of water boiled to the surface and sprayed up into vast fountains astern of Starling. The great cascades subsided; but of the U Boat there was no sign. Walker settled down to the waiting game. The enemy was proving tough to hold and hard to find. During exercises, Walker had evolved a form of attack known as Operation Plaster. It called for three sloops steaming in line abreast to roll depth charges off their sterns. Now he ordered Wild Goose and Kite to join Starling, and the three sloops steamed forward dropping a continuous stream of charges, the naval equivalent of an artillery barrage before an infantry attack. The sea heaved and shook under the impact of the explosions. |

HMS Starling during a "plaster" attack, Walker in command. (Caption reads Winter '44 - this means early '44 as Captain Walker died in July 1944) |

| Twisting and turning and always leaving a trail of charges, the ships plastered the area. In three minutes, 86 depth charges had rocked and shaken the attackers almost as much as it had U-202. The U Boat settled deeper and deeper, the control room crew watched the depth gauge. Down to 700. Much more and the submarine would crack under the tremendous pressure. 750. Poser's eyes would have been fixed on the controls, and his mind listening to the creaks and groans reverberating from the straining hull. 800, the engineer officer's will have warned. 850. Poser snapped out his commands: "Level off and keep her trimmed at 800 feet. Steer due north, 3 knots." Far above, Walker was talking to his officers: "No doubt about it. She's gone deeper than I thought possible, and our depth-charge primers won't explode below 600 feet. Very maddening indeed." He grinned and continued: "Well, long wait ahead. Let's have some sandwiches sent up. We will sit it out. I estimate this chap will surface at midnight. Either his air or batteries will give out by then." It was shortly after noon on June 13. By 8 p.m. Poser had taken several evasive turns without result. He could not shake off his tormentors. At two minutes after midnight his air gave out. He ordered reluctantly, "Take her to the surface." Without any audible warning, U-202 rose fast through the water to surface with bows high in the air. Her crew leaped through the conning tower hatch to man her guns, and Poser shouted for full speed in the hope of outrunning the hunters. On Starling's bridge, the tiny silver conning tower was visible in the moonlight. "Star shell...commence," ordered Walker. One turret bathed the heavens with light. Then came a flashing crash of the first broadside from all six sloops laying a barrage of shells around the target. A dull red glow leaped from behind the conning tower of the U-boat. |

|

| A dimmed lamp blinked from Starling, and firing ceased while Walker increased speed to ram. Then he saw the jagged stump of the conning tower ablaze and shouted in triumph. U-202 was obviously too damaged to escape. He ran alongside, raking her decks with machine-gun fire and firing a shallow pattern of depth charges that straddled the submarine, enveloping her in smoke and spray. Poser clutched the hot periscope column, drew his revolver and shouted a last order: "Abandon ship! Abandon ship!" The cry was taken up and passed through the U-boat. Poser turned to say goodbye to his officers. But he found they too had all abandoned ship. So he dived into the sea, intend on their reprimand when the war was over. He had fully intended to die rather than be captured. At 12:30 a.m. the battle was over - 16 hours after it had begun. |

| (This episode in the life of Walkers Escort Group is captured on video "Battle of the Atlantic" which I purchased from the Mersey Ferries Shop on the Pier Head, only a few yards from the statue of Captain Walker himself. Also on this tape is the homecoming of the Group after the famous "6 in one trip" plus the funeral and burial at sea of Captain Walker.) |

|

When the Second Support Group returned to Liverpool with U-202 and two more killings to its credit, Walker learned that his elder son, Timothy, had joined the crew of a British submarine, operating in the Mediterranean. The following month, Admiral Karl Döenitz, commander of the U-boat fleet, threw 150 U-boats against the increasingly busy Atlantic convoy routes. Johnnie Walker again led his striking force into the Bay of Biscay to meet the enemy at his departure points. On July 29, alerted by aircraft, the enemy came in sight on the horizon, three conning towers in line ahead. Walker's inherent love for the dramatic came to the fore. He beckoned to the signalman and ordered, "Hoist the General Chase." For a moment the signalman was confused. Then he ran up a signal used only three times before in the history of the Royal Navy, including Admiral Horatio Nelson at the Battle of Trafalgar. Off the leash at last, the five British sloops sallied forth. |

General Chase pennant (photo: R Holden) taken in Bootle Town Hall |

| On Starling's bridge, Walker waved his cap in the air as though urging her to greater efforts as the guns of the entire group thundered a broadside at the unsuspecting U-boats. In 30 seconds, all three had been hit from a range of four miles, making diving impossible. Ten minutes later it was all over. In August, Johnnie Walker took his ships back to their Liverpool base. He was steering Starling through the tricky lock gates when a signalman reported, "There is someone ashore waving as though he wants to come aboard urgently, sir." It was an officer from Sir Max Horton's staff. He jumped aboard and ran to the bridge where he saluted Walker and said, "I have been ordered to report to you, sir, that your son Sub Lieutenant John Timothy Ryder Walker RNVR, is reported missing as at 10 August 1943 while serving in a Mediterranean submarine." Eileen Walker arrived just after the ship had made fast. |

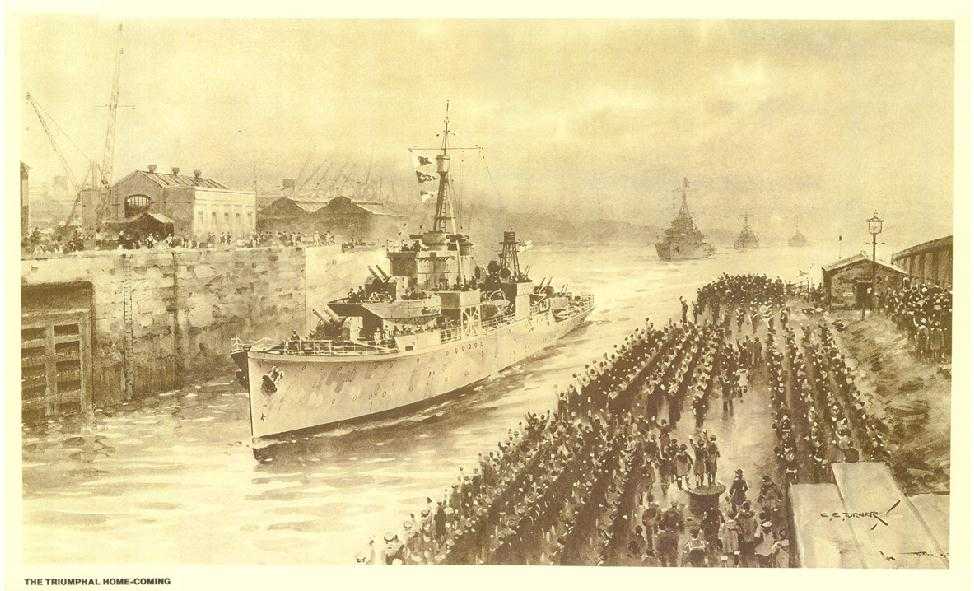

| The gathering of people with urgent business to discuss with Captain (D) found a solid block of ship's officers between them and their target. His officers and their wives had invited Captain and Eileen Walker to dinner in the wardroom the following evening. These were very special events, much valued as occasions when it was possible to forget for a while the discomforts and lack of social life at sea. The suggestion to postpone the date was rejected by Captain Walker and the dinner party took place as planned. But it was quieter than usual and Captain Walker didn't do his usual dinner party trick standing on his head drinking a beer! The war had never been closer to Starling and her crew as that night. In a two-week hunting strike following this news, Walker's group sank six U-boats, claimed two more probable and damaged another. It was never revenge but a dogged determination to rid the world of Nazi Germany. See 6 In One Trip. The image below depicts the ships returning home to a tumultuous welcome from Liverpool. And a speech from the First Sea Lord himself on the dockside. |

Image Right: This was an actual photo of the depth charges being set to "shallow" as the torpedo homed in on Starlings stern |

|

|

It was a tremendous achievement made all the greater because those were the days

when German scientists had equipped their submarines with torpedoes that homed

on propellers and followed an attacker no matter how he twisted and turned to

evade them; and the snorkel, a breathing device that enabled U-boats to stay

under water for prolonged periods. The first of the six kills was U-264, commanded

by Kapitänleutnant Hartwig Looks, a veteran submariner. Shortly after

dawn one morning, Looks sighted the Second Support Group through his periscope.

As the sloops passed, he fired a torpedo in the general direction of the nearest

- Starling. On the sloop's bridge, Walker spun around at an

excited shout from a lookout to see the track of the torpedo approaching his

stern, homing on the propellers. There was no time to increase speed or to take

violent avoiding action. His mind raced. Starling was doomed. With eyes fixed on

the line of bubbles, he rapped out orders: "Hard aport....Stand by depth

charges....Shallow setting....Fire." (see above right) Suddenly the air was rent by two almost

simultaneous shattering roars. The first came from the depth charges and the

second, from the torpedo, which had gone off 5 yards from the sloop's

quarterdeck. The depth charges had countermined the torpedo a second before it

struck. Walker led the sloops in a plaster attack. The pounding barrage was kept

up for five minutes before the evidence of success appeared--a huge air bubble

that collapsed to spread chunks of wood and human remains over the sea. Once in

the approaches to Liverpool, tension sapped away. The men were worn-out but

happy. In this mood the sloops arrived off Liverpool to be met by a destroyer flying the flag of Sir Max Horton. A brief exchange of signals revealed that also aboard was the First Lord of the Admiralty, the then Right Honourable A.V. Alexander, later to become Viscount Alexander of Hillsborough. The destroyer's crew waved and cheered the proud line of sloops into the harbour as they maintained station as rigidly as guardsmen, with ensigns flying stiffly in the breeze. Walter was promoted to Captain, and a galaxy of medals (six in all) fell into his possession. (Again, this is portrayed on film on the video "Battle of the Atlantic" and shows all ships company's assembled for the welcome home) He looked forward to rest, his future assured. It was not to be, however. Scientists wanted an experienced seaman to take them on a hunt for enemy aircraft armed with guided-missile bombs, nicknamed "Chase-Me-Charles." So after only three days in Liverpool, Walker led his ships back to the Bay of Biscay, to patrol well inshore under the enemy guns to entice rocket-firing aircraft into the air. In one day, the sloops were subjected to 12 Chase-Me-Charles attacks, a hair-raising experience because the scientists, experimenting with a device for breaking the radio contact between the aircraft and the missile, were upset at the thought of shooting anything down. On the third day, two missiles were fired at Wild Goose within seconds of each other and, after wobbling on a proper course straight for the sloop, suddenly fell into the sea. A Close Shave! One scientist thought this significant and asked Walker what electrical machinery was running then that would not have been running during earlier attacks. Investigation revealed that one of Starling's officers had been shaving at the time, using an electric shaver. Excited, the scientist begged Walker to sail even closer to the French coast to coax a further series of attacks. Walker did so, and the Luftwaffe sent up a squadron armed with orthodox bombs and guided rockets. As the planes came in low and launched their rockets, four electric shavers--all the group could muster--were switched on. Every rocket swerved off course and crashed into the sea. Another version states that the scientists ran electric razors over microphones in an attempt, successfully, to thwart the radio signals from the parent aircraft. (The Fighting Captain - Alan Burn). Some incidents also occurred with Spanish trawlers, which were trying to mask U-boat movements in the Bay of Biscay. These were sunk and their crews taken off. Many of these Spanish sailors begged to be allowed to stay onboard and become "Hostilities Only" British sailors. But Walker later repatriated them via another Spanish trawler. One Spanish Captain was asked how he felt about his trawler being sunk, he shrugged his shoulders and muttered that it belonged to Franco. |

|

HMS Starling was constructed at the Fairfield Shipbuilding and Engineering Company in Govan, Glasgow and was launched in October of 1942. Completed on April of 1943, she sailed from Liverpool under the command of Captain F J Walker Commander of the 2nd Escort Group. In her career she was responsible for the sinking of 14 U-boats. She met her end, not in battle, but at the scrapyard of Lacmots Ltd and was scrapped in July 1965. |

|

|

| The activities of the Group were as high as ever but had no sightings of U Boats. The ships were to come to the aid of down aircrews in the Bay of Biscay, but on occasion, they would be too late. There were 9 crew in a Liberator and Liberator P/224 was shot down attacking a U Boat. 2 were killed as they pressed home their attack on the surfaced U Boat. Of the 7 in the dinghy, two died having been refused water by a U Boat that came alongside and spoke to them. After 8 days, the five survivors were brought on board Wild Goose in a very bad state. 2 more died on board after making their reports. For the first time bitterness crept into the attitude of the ships companies. |

| At sea nobody wore a semblance of uniform. But it was custom to enter harbour in style with the ships line ahead, hands on deck in their No 1's, guns trained fore and aft with their crested caps in place, ensigns flying and "A Hunting we will go" the groups signature tune, blaring from the ships speakers. Captain was in full uniform standing just behind the binnacle as we entered Plymouth. As the ships approached the lighthouse a small coaster came into view, plodding clear of the ships and to port of the main channel. "We could see the men on the bridge watching us, why not? We were a fine sight" One of these men was waving at Starling and one of the officers picked up his binoculars and took a look. "ENOS! No it can't be" exclaimed the Officer. "Captain Sir, what do you think of that fine ship? That's my father waving". "What's he doing there, Alan", replied Captain Walker. "He goes to sea sometimes to deliver these little ships. He told me in his last letter that he would be bringing this one down from Glasgow about now". |

| Captain Walker called to his Yeoman "Signal - Disregard My Movement", Ask Petty Officer Gardner to bring up a bottle of gin, Number One. I'm going alongside to pass over that bottle. Port 15". Starling pulled gracefully out of her position at the head of the line. Leading Seaman Smith appeared below the bridge, alongside B gun, with his heaving line. He was a big heavy man and no one could throw a line like he could. The bottle went across, the other ships steaming past on their original course, dozens of binoculars watching every move. The Yeoman leaned over the bridge, waving hands to his opposite numbers on passing bridges, keeping all informed. Inside 2 minutes the story has passed through every crewman right down to the engine rooms. "Get me back in station Pilot. We must be there before we get to the Melampus buoy, or I shall be in trouble". There was a half smile on Walker's face. It was quite clear that this bit of fun had made his day. "Now Pilot could do a bit of quick ship handling to drop Starling back into place, ahead of the line, without leaving the channel or running aground!" |

Modern day Plymouth Hoe |

| In March, Walker and his group were assigned to escort a unique convoy to Russia - unique because the most valuable ship of them all was the U.S. cruiser Milwaukee. She was a gift from President Franklin D. Roosevelt to Josef Stalin, and although sailing with an all - American crew, she was placed in the care of the Royal Navy for the voyage. Walker sank two more U-boats on this trip, and Milwaukee was duly delivered. She was handed over to the Russians, who renamed her Murmansk, and the British group sailed for home with the American crew. On the way back, a spate of urgent signals indicated that U-473 had torpedoed and sunk the American destroyer Donnell about 200 miles away. Having enjoyed his recent experience of working with Allies, Walker promised his passengers to seek out and avenge their compatriots. It was a classic hunt. Although the enemy could be anywhere within a radius of 200 miles, Walker drew on his vast knowledge of U-boat tactics to calculate several possibilities. He chose the enemy's most likely course and moved to interceWalker hunted the U-boat for 23 hours in a nervy, protracted wait punctuated by clouds of gnats that sent them scudding in all directions. Always they managed to regain contact. Once again it was the lack of air that forced U-473 to surface, and again the combined fire of the group sent a U-boat to the bottom. Honour was satisfied. Donnell was avenged. When the hunters returned to Liverpool, Eileen Walker was aghast at her husband's haggard appearance. The toll being taken of his strength and resistance frightened her. Walker was killing himself, gradually and inevitably. Two days later, U-473 stalked a fresh area of operations and found the Second Support Group already there. U-473 proved to be a slippery opponent. |

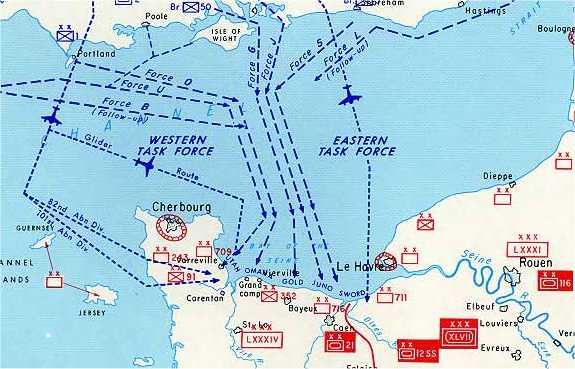

U Boat under Air Attack |

| General Eisenhower, the Allied commander in chief, had decreed that the Normandy invasion forces--and if possible the entire English Channel--must be free from the threat of massed U-boat attack for the D-Day landings to succeed. From D-Day to D-plus-14, the assault forces would have to be landed safely, the beachhead consolidated, and the build up of supplies assured. On June 6, D-Day, 76 U-boats sailed from their Biscay bases into the Channel to disrupt the landings in Normandy. As sighting reports streamed into Starling, Walker said: "Eisenhower wants two weeks. He'll not only get it, but this is our chance to smash the U-boat arm for all time." In those first three days, he directed his 40 ships into no fewer than 36 attacks, during which eight U-boats were destroyed and many more damaged. Aircraft claimed another six, and the first enemy wave withdrew. |

|

| The U-boats returned later for another desperate effort to penetrate into the Channel, and for a week there was no rest for men or ships. Each time it was Starling's turn to retire for new ammunition her crew snatched a few hours' sleep. But not Walker. He attended conferences, adjusted tactics, laid new plans and with seemingly inexhaustible energy took his ship back to sea to resume the struggle. Only a handful of U-boats needed to reach the landing area to create the havoc that would give the enemy vital respite. The two weeks demanded by Eisenhower passed without a single U-boat getting through. In the third week, three slipped past the defenders and caused a moment of panic among the great invasion fleet, but they were quickly destroyed. After three weeks, the U-boats withdrew again, unbelievably mauled. They were never to return in strength. Walker had achieved his final ambition, the destruction of the U-boats as an integrated fighting force. The Battle of the Atlantic was won; the Battle for the Channel had never been lost. Even Walker's own officers were becoming alarmed at the grey, drawn face of their captain. His eyes had sunk back into a gaunt face that was itself little more than skin stretched across bones. His lean frame sagged, and his normal decisiveness was being replaced by growing hesitancy and an uncertain search for the right words when sending signals. Yet no one could foresee the end. Johnnie Walker's name was acclaimed in the press alongside those of the "glamour" boys, Montgomery, Mountbatten, Patton and Bradley. Nowadays I would place him alongside Sir Francis Drake and Admiral Nelson without a second thought. |

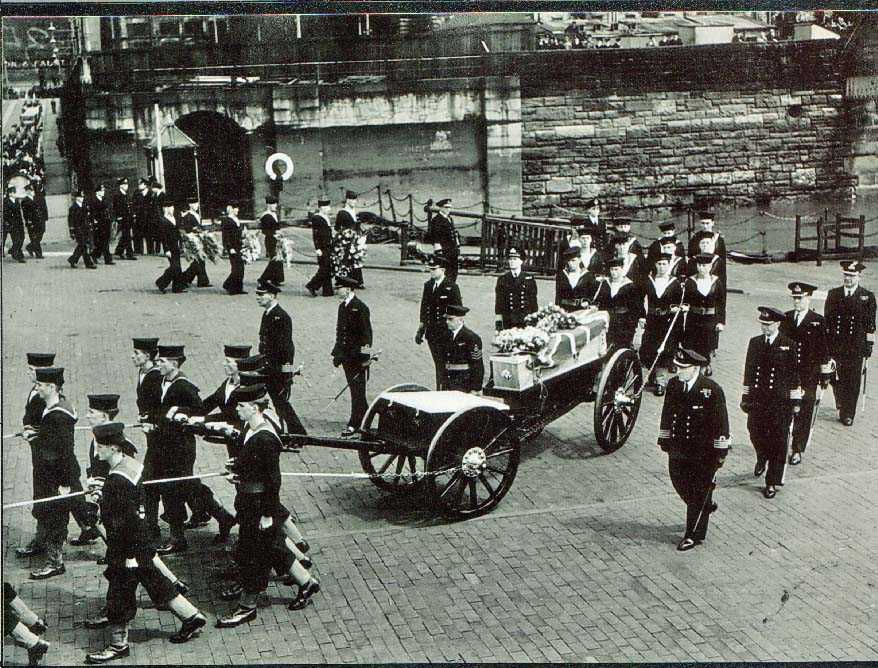

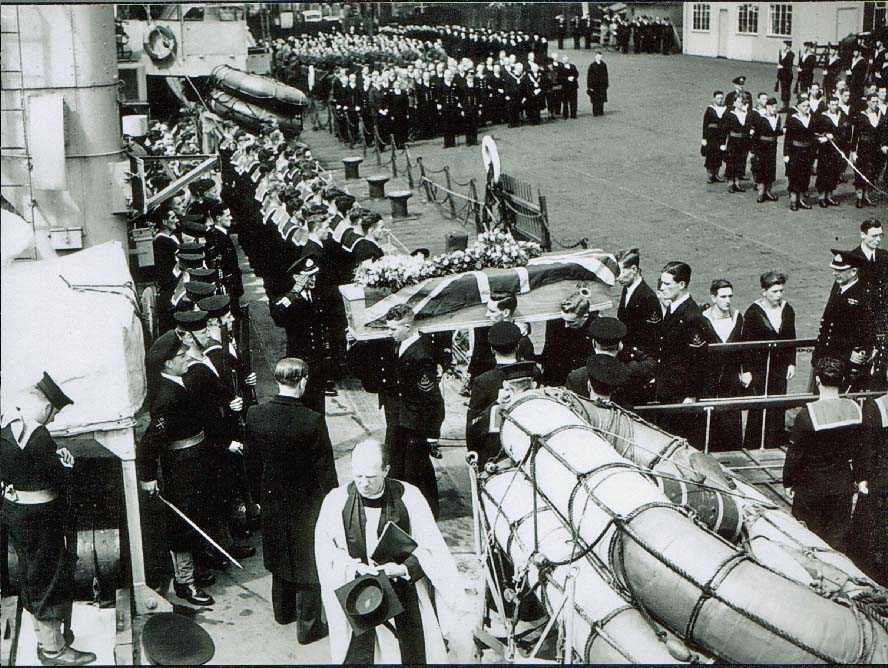

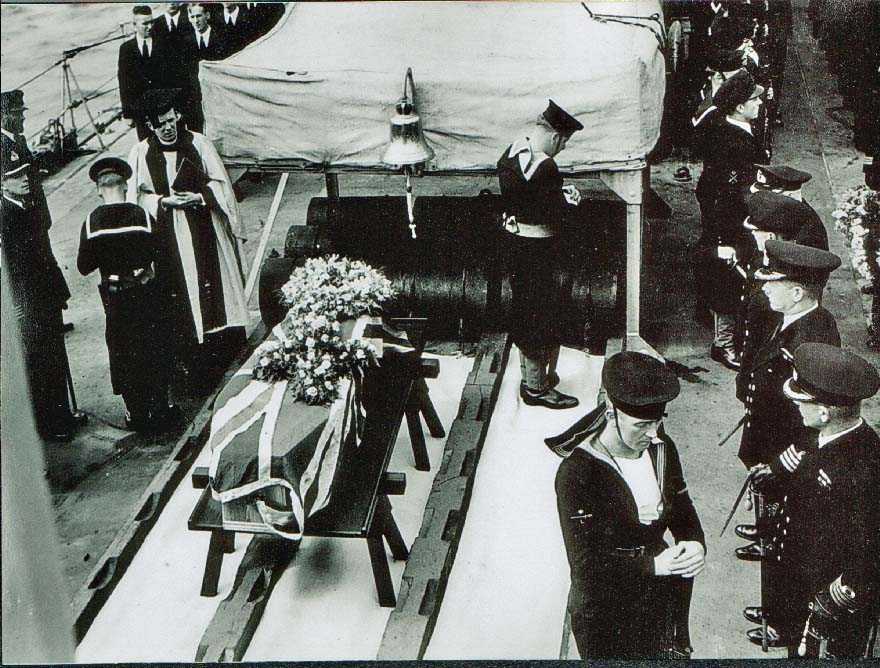

| An Admiralty representative called on Eileen at her Liverpool home to relay the news that her husband was to be knighted by King George VI. Now, she thought, he will have to take a rest. The afternoon following his arrival home, the couple went to the movies to see Madame Curie. Afterward, he complained of giddiness and a curious humming noise in his head. At home he was violently sick, and the giddy spells returned. Walker was rushed to the hospital and immediately examined. "All your husband needs is quiet and rest," Eileen was told. But the next day it became apparent that something was seriously wrong with Johnnie Walker. The news that his life might be in danger spread throughout the whole command. At midnight on July 9, 1944, Eileen was summoned to her husband's bedside. It was too late. Captain Johnny Walker was dead. Officially he died of a cerebral thrombosis. In fact, he died of overstrain, overwork and war weariness; his mind and body had been driven beyond the normal limits in a life dedicated to the total destruction of the enemy, revenge for his son and to the service of his country. Captain Walker's solemn funeral is captured on film in the video "Battle of the Atlantic" available from Mersey Ferries Ship on the Pier Head, Liverpool. And from HQ Western Approaches, Derby House. (Video details above). I have received some new prints of Walkers funeral from Robb Webb, son of Frank Webb HMS Kite. |

Walker disembarks |

|

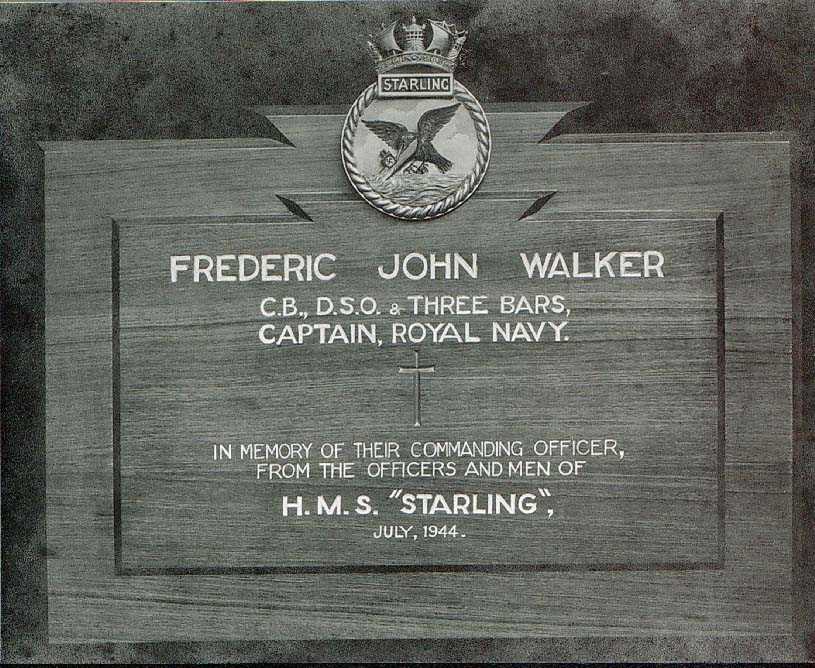

Leading Head Bearer, nearest the camera, is William Ruffley. Thanks to his son, Tom, for that information. William survived the first Battle of Narvik in 1940.  HMCS Iroquois formed the Honour Guard marching behind the coffin  The bearers and parade were provided by Canadian sailors docked in Liverpool, and the crew of HMS Hesperus, a destroyer. Walkers gallant ships had already sailed and were on operational duty at this time   HMS Hesperus in action against a U Boat - Thanks to Wayne King (Ex RCN) for this painting |

|

ASDIC Operator |

|

A Note on Asdic: In 1917 Germany claimed 8 million tons of allied shipping sunk by U Boat. In only 3 years of war. The lessons clearly had not been learnt. Britain fully expected the main threat to come from surface ships. Too much confidence had been placed in ASDIC, the Navy’s underwater “eye”. Churchill, having seen a demonstration for himself, in calm waters, also placed too much emphasis on ASDIC. The truth was far from it. ASDIC did not like foul weather, could detect underwater shoals of fish, the seabed and wrecks. The operators had to distinguish between the difference signals being received. Yet for all this confidence, too few ships were equipped and too few operators trained to use it well. Snobbery within the service also took its toll; the Anti Submarine Unit was seen as a bit of a “Cinderella” service. Admiralty had difficulty persuading young officers to join. Too much faith had been put in ASDIC, a submarine on the surface was virtually undetectable. “I don’t remember ever being taught the WW1 submarine tactics”, said ASW specialist, Maurice Usherwood, “I was expecting them to remain at periscope depth and attack from there”. The importance of air power towards the end of WW1 showed clearly fewer losses than those without and yet the Admiralty’s faith in ASDIC was so strong that it deemed aircraft to be no longer essential in this role. The idea of old “stuck in the mud” staff officers who thought that they knew better comes easily to mind. (My Comment) The Battle of The Atlantic - Andrew Williams (BBC). |

Liverpool Maritime Museum . HF/DF Set. Image M Kemble February 2008 Liverpool Maritime Museum |

| HF/DF (High Frequency Direction Finder) was used by Walker and many others to triangulate a position of transmitting U boats, enabling ships in locality to hunt and usually destroy the submarine. One of Doenitz's big mistakes in WW2 was to demand regular weather reports from his subs to enable German Luftwaffe to project their bombing raids on England. Thus causing the deaths of many a crew. |

|

Sonar: Sonar is a system for detecting submarine sound in the water. It was first developed by the British for use against U-boats in World War I. Radar uses radio waves to detect objects on and above the land and sea surface. Radar was developed in the 1930’s to detect aircraft. Both sonar and radar technology matured during World War II, and both were used by the Allies to combat German U-boats. Sonar and radar were also added to Allied submarines to warn of aircraft attack and counterattack from surface vessels. Since World War II sonar has been the most important of the submarine’s senses. Hydrophones are the submarine’s ears, and they listen for sounds from other ships and the echoes of sound waves transmitted from the submarine itself.

|

|

Starling - Ships Bell - July 8th 2003 Bootle town Hall. Model of Starling in the Maritime Museum, Albert Dock, Liverpool July 8th 2003 |

HMS Wild Goose Battle Flag - The white shapes denote conning towers and barely seen in the bottom left hand corner of the flag is a red cross and a polar bear on an ice floe. These denote a hospital ship accidentally shelled and also the "accidental" shelling of a 'Nazi' Polar Bear! |

|

HMS Wild Goose - this image was taken from HMS Tracker |

| If there is one single thing that stands out in all my research on both the Royal & Merchant Naval histories in World War 2, it is the constant NON references to the fantastic bravery displayed by these lads who were "just doing their job". So much was accepted as the "norm", so much heroism passed by as normal! A very good example of this is Walkers crews on his sloops. These ships, lets face it, were so small that a half decent torpedo would rend a ship in half, sinking her in seconds as so cruelly displayed with HMS Kite in 1944. The crews were so well drilled that the ships were an extension of themselves, part of them. When the ship hurt, they hurt, when the ship bled, they bled. My feelings towards what these fantastic men (and women too) did for us in World War 2 is immense. I wonder if they would have "bothered" if they knew what the future was to become? |

|

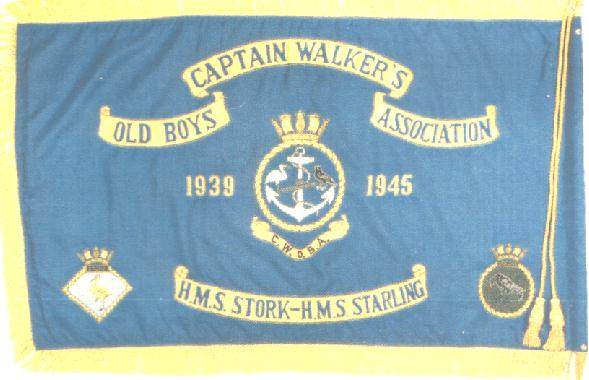

| Captain Walker's Old Boys Association

attended their last function on Saturday 10th July 2004 at the Pier

Head where they handed over the statue of Captain Johnnie Walker to

the safe keeping of Liverpool Council and the people. Following on

from this they all attended a service a St Nicholas' Church before

moving on to Bootle Town Hall where the Association standard was

formerly handed over to the Deputy Lord Mayor of Sefton for keeping in

a permanent purpose built case in the Town Hall. Captain Walker's grandson, Captain Pat Walker CBE, presided over the events and we all had a most enjoyable day. The CWOBA once had their own web site which folded, coincidentally, as my own pages on Captain Walker were begun. Although I have nothing to do with the Royal Navy, and especially of that era, I now look after the only, fully informative site on both Captain Walker and one of his ships, HMS Kite. Which is why I was invited to attend. The stories these people could tell would make your hair curl and yet, at the time, they just got on with it without too much fuss or bother. Reading something that happened in history is all very well but to hear how life was actually like for these sailors, and the hardships endured, makes for a much more interesting read. I have some on my site but always touting for more info! Captain Walker's Old Boys Association is now a part of history. Using Liverpool as a base, they scoured the high seas, in those Black Swan class Sloops, hunting for the elusive U boat. Their success in this is now the stuff of legends. Included in their patrols is the story of them catching and sinking 6 U Boats on one single patrol. Their heroism is clearly depicted in the Maritime Museum in Albert Dock and also in Bootle Town Hall, with their battle ensigns and other memorabilia on the walls of the Council Chamber as well as the entrance and hallways. Each Council Meeting is called to order by the ringing of Starling's Bell. Their numbers dwindle yearly, and now they feel it is the right time to "hang up the flag" and gracefully recede into the sunset of their lives. The gratitude of the people of Liverpool, the United Kingdom and thousands of surviving sailors all over the world is their reward. A photographic record of this day can be found here: |

|

|

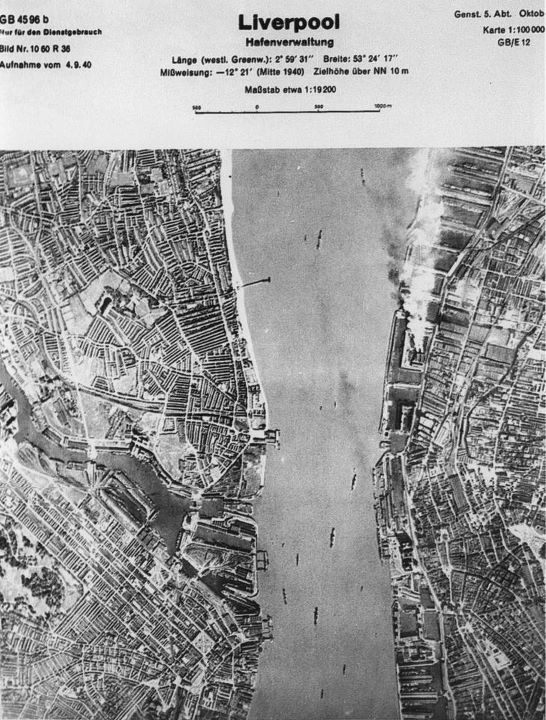

A Luftwaffe recce photo of the Mersey. Note smoke from power station on Lpool docks |

HMS Wren HMS Whimbrel (Click on image for news story) Update Here |

HMS Nereide Sloop Modified Black Swan Pennant Number U64 Built Chatham Dockyard Laid Down 15th Feb 1943 Launched 29th Jan 1944 Commissioned 3rd May 1946 Scrapped 18th May 1958 |

HMS Woodcock HMS Woodcock off Gladstone Dock, River Mersey |

HMS Kite (Click on image to go to Kite's own pages) |

HMS Mermaid. Picture was taken in Valetta Harbour after the war (1956?) |

Mermaid |

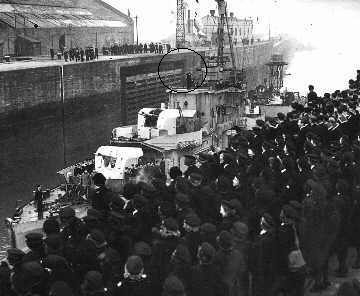

Starling (Walker circled), after sinking 6 U Boats ** (See base of page) |

|

Starling approx 1957 |

|

|

| An interesting note from Ray Holden. "Have been making some comparisons with these two images, the unknown location one tells me that it was taken sometime between June and September, how do I know? because the ratings on the fore deck although dressed in blues are wearing white fronts, summer dress. I feel that she was just back from a convoy run by the state of her paintwork, any ideas, Could it be the entrance to the Mersey? In the Malta version her HF/DF Radar mast has gone, the one with the square box on top, so has her Crows nest which has been replaced by a Radar Plot system. The Director Control Tower looks very much the same suggesting that her gunnery system was basically the same but note the rocket launchers on B gun turret. Talking about this gun turret, this image shows that it is some distance away from the bridge so Lt Com. Segrave (HMS Kite) didn't fall off it, he fell down the back of it. Looks as if Lionel got it wrong, Lt Comd Segrave was standing on the Wind Baffles which run along the top edge of the bridge which seems to have been a popular position for Commanding Officers." |

|

August 2006: Ray Holden has come up with another prize: This time a letter from Admiral Gunther Poser to a Mr Jarvis in October 1990:

|

|

In November 2017 I received an email from Manuel Ortega about his

fathers encounter with Capt Walker. Manuel Fernando Fernandez Ortega. He was Spanish, born in 1923, and being a man-of-sea since 14 years-old in merchant navy, when he need to serve military in Spain, he choose Spanish Navy. He fulfil his duties starting aboard F22 TRITON, a minesweeper of Spanish Navy as helmsman in 1943. And this is when Captain Walker life's cross with my father´s life ! I remember he tell me that, despite fact Spain as a neutral country in WW2 (not so neutral we know) and Spanish´s ship used neutral marks, they were politely intercepted by a English sloop-of-war in Bay of Biscay. My father tell me captain of English ship was received aboard by Spanish´s captain, he was very polite and very professional, and my father admired so much the way things were conducted by English´s captain in a peaceful way. I asked to my father WHY they were intercepted if they were neutral, and he tells me F22 TRITON (his ship) have a great resemblance with Nazi Germany´s ships, apart fact they were in Bay of Biscay waters at the time. |

|

|

Chris Elsden is an artist who has kindly consented to

allow me to display one of his paintings, this of HMS Starling In The Atlantic. |

|

A Summary of U Boats sunk by 2nd Escort Support Group http://shipsnostalgia.tv/action/viewvideo/1695/Captain_Walker_s_funeral/ http://shipsnostalgia.tv/action/viewvideo/1696/Starling_arrives_Liverpool/ Sources and Referrals http://www.britishpathe.com - I downloaded a free video of the 6 In One Trip Homecoming from this site, its about 3078kb long, low resolution, and very watchable. It lasts about 3 minutes. Thanks to Ray for finding it. Entitled U Boat Killers. Some stills from the video are shown here:

|

|

| U99 Report on Interogation of Prisoners | |

|

|

Books on Johnnie Walker & Related Subjects: The Fighting Captain by Alan Burn - still in

print. I got my copy from

www.amazon.co.uk The 2nd Edition of Escort Carrier includes HMS Vindex at war; she worked closely with the 2nd Support Group and one paragraph is relating to the sinking of HMS Kite. All these books may be available on the net. |

|

|

I help you with information, please help me. I need funds to keep this site going. Donations can be sent via my paypal button, it is easy and its secure. Email me if you want to send a cheque. And thank you. Paypal is on my front page www.england.cam |